Throughout the British Caribbean, the apprenticeship period failed its primary objective of preparing the ex-slaves and their employers for a harmonious free labour economy. This was mainly because of the intransigent and hostile actions of the planter class and the weakness of the mechanisms put in place to protect the apprentices.

In the British West Indies, the Abolition of Slavery Act 1834, granted slave owners £20 million compensation for the loss of their slaves. It also rewarded them by introducing an apprenticeship period. In practical terms, however, only slaves below the age of six were freed.

"Putting it simply Britain, were saying to the plantation owners, we going to put an end to slave labour but because they were your property and livelihood we will compensate you for your loss and to help you adjust to the change we will let the free people work for you for free for another 4 years."

Slaves were to be divided into two groups, praedial (attached to land) and 'non-praedial' workers. The non-praedial workers were to be fully freed in 1838, four years after the abolition of slavery and the praedial workers were to be apprenticed for an extra two years. The apprenticeship period meant that slaves had to work unpaid for just over forty hours per week, this was their training for full freedom.

African-Caribbean women during slavery were judged by Europeans as unfit and unfeeling mothers. They were accused of extreme cruelty, and neglect, preferring to attend dances than care for their children.

Women formed the majority of the field labourers at the time of emancipation and therefore were vulnerable to exploitation by overseers and managers. Plantation managers were reluctant to relinquish the power that they had enjoyed during slavery, and they particularly didn't want to lose the power that they held over the bodies of black women. African-Caribbean women were forced into the roles of breeding stock and sexual partner for the planter class, but were denied any rights to their children or to learn trades which would class them within the slave elite.

Planters were well aware that when fully free, women and men would adopt new customs that would remove women from the fields and the overseers' control. They therefore did everything in their power to tie them to the plantation. Pregnant women were singled out for abuse. They were expected to carry out strenuous work even when heavily pregnant and were not given the lying-in time that slave women had received. Some were even denied medical care during their pregnancy.

During slavery, a series of jobs had been created to occupy elderly and weaker slaves and ensure the smooth running of the plantations. One such job was that of nurse for babies and young children on the estate. While mothers worked in the fields, their children were looked after by these women. These nurseries were often abandoned when the planter no longer owned the children; mothers were expected to look after their children and work a full day in the fields. As a result of the closure of nurseries, women with young children were constantly late for work and many had to take their infants into the fields with them.

In drafting their Abolition Act, St Vincent legislators had attempted to increase their power over free children by stating that if a parent could not care for a child, he or she should be apprenticed to the estate until the age of twenty-one. This was one of the clauses that the Assembly was forced to amend before their Abolition Act was passed. Planters resented their lack of control over the plantation children and the fact that the work once performed by `piccaninny' gangs now had to be done by adults.

"You see how smart they were? By closing the nurseries it was almost impossible for a mother to look after her child and work at the same time"

The St. Vincent Assembly made other attempts to regain legal control over the children's labour. In 1836, during the debate on the establishment of a free school in the colony, the Assembly recommended that schooling should be made compulsory for children. In addition, they recommended that it be paid for by either demanding extra work from all the apprentices, or by having all children over the age of seven work four days a week on the estates.

"Lord these people were something else!"

Infant mortality was high but was not the result of neglect from mothers, but due to the conflict between mothers and their estate managers. There had been an island wide outbreak of measles and many mothers had feared that by taking their children to the estate hospitals or by consulting the doctors, the estates would have a claim on the children's labour. Consequently, a large number of children had died from the disease. However, because of improved labour relations, many parents had agreed to work extra days on their estates in return for free medical care for their children. The usual agreement was that each year, one of the parents would work six extra days for their first child and nine days if they had more than one child.

Out of twenty estates, twelve had made agreements for the parents to give extra labour for the doctors' fees and on the other estates the parents had decided to pay the doctors themselves if their children were ill. Usually, it was the mothers who agreed to do the extra work to cover the fees.

African-Caribbean women during slavery were judged by Europeans as unfit and unfeeling mothers. They were accused of extreme cruelty, and neglect, preferring to attend dances than care for their children. For example, Mrs. Carmichael, a slave owner in St. Vincent, maintained that her slave women were unnatural and cruel to their offspring. She wrote: 'Negro mothers, with only one exception, I have found cruelly harsh to their children, they beat them unmercifully for perfect trifles. ''

By 1837, only three children had been apprenticed, and these children came from families with extreme problems of alcohol addiction. Infant mortality during the apprenticeship period was high, but not as high as during slavery.

Apprentices reacted both individually and collectively against the planter's unfair management. Some attempted legal means to achieve better conditions. A few individuals also chose to pay for their freedom, some for quite large sums of money. From August 1834 to September 1835, forty-two apprentices were released by the magistrates in St. Vincent. Of these, nine males and eleven females were freed in return for payment. The sums paid were considerable. The highest price for males was £175.3s and for females it was £120.

Many planters resisted apprentices attempts to buy their freedom and, in this, they were aided by the local Abolition Act. The St. Vincent Abolition Act made freedom in a disputed case especially difficult for apprentices. In clause 10, the Act stated that the appraisal price had to be paid immediately or was made void. This contravened the Imperial Act, which allowed the apprentices one full week to find the money. Therefore, if the price of an appraisal was slightly higher than the apprentice expected, he or she could not have time to find the extra money.

There is little evidence from apprentices why they chose to pay for their freedom when there was such a short period of time remaining before the total abolition of slavery. In some cases, excessive cruelty was the obvious reason. However, we can only speculate on the motives of the other apprentices. Some apprentices probably did not trust the white community. They may have taken the opportunity to pay for their own freedom in the expectation that slavery would be re-established as it had been in the French Caribbean.

Rumours that slavery would be re-introduced swept St. Kitts, St.Lucia and Dominica during the first decades of freedom, which indicates the lack of confidence that the freed people had in the white authorities. For some apprentices, this was their first opportunity to gain some control over their own lives. It enabled them to actively resist the plantocracy, rather than remain passive. Apprentices who could raise the money to buy out their time could join their families and friends and couples were able to live together.

Some, in particular women, chose to become independent of the sugar estates. Others chose to change their employers by agreeing to indenture themselves to work on a different plantation in exchange for their appraisal price. For other apprentices, it may have been a matter of personal pride. They earned their own freedom rather than received it as a gift. During the few months before the final abolition of the apprenticeship, many people bought their freedom because they did not want to be seen as a 'fuss of August nigger'. They wanted to gain for themselves and their family the status of free blacks and coloureds.

In Kingstown, apprentices were often hired out as domestics, skilled workers and higglers, and women were also expected to work as prostitutes. Poverty was extensive and some observers in the West Indies claimed that, in the towns, women sometimes were denied food and clothing allowances and lived in destitution. On plantations, the most common offences involved the withdrawal of labour, either by running away, turning out late or working 'indolently'. Women predominated in these cases because they made up the majority of field workers and because many had additional domestic duties and had to oversee the care of their children as well as work on the estates.

Women were always remarked on for being the most abusive within the plantations. It was often the female slaves who led the insults aimed at the bookkeepers and other white estate workers, and during apprenticeship this remained the case.

The destruction of property, however, was primarily an act of male defiance. The majority of arson and vandalism cases were committed by men. Planters especially feared cane burning because of the physical and financial damage it could do and therefore it was often punished by the Supreme Court rather than the magistrates, with the death penalty for those found guilty. When the magistrates could not ascertain who was responsible for setting a fire, they punished the whole work force with extra labour.

The managers decided to change the working hours and forms of payment to suit their own needs without reference to either the previous agreements or the stipulations of the Governor.

Group actions were also common. Throughout the apprenticeship period, there were sporadic protests on the plantations and the district most affected was the Kingstown district. In 1837 a group of women apprentices complained that they had not received any of their free days because the manager sent a group of them each week to the stipendiary magistrate with complaints, and he responded by sentencing the whole gang to work on their free days. One of the apprentices, a woman called Madge, further claimed that the magistrate, John Pitman, also refused to allow any of the apprentices to speak in their defence and threatened to beat any who attempted to protest.

The use of punishing whole gangs had been used as a means of extracting unpaid work from apprentices. It reveals that planters resented paying their labourers as well as allowing them the choice of working on the estate or devoting additional time to their provision grounds. Apprentices had learnt to mobilise themselves as a group during the slavery period. In St. Vincent, the last slave protests took place on several estates in the Carib district of the island.

The apprentices from three of these estates staged a similar protest during the cropping period, in early March 1835. The dispute occurred when the managers of Orange Hill, Turama and Waterloo estates decided to change the hours and method of payment during the busy crop period. Lieutenant-Governor Tyler had suggested that during cropping, the apprentices should earn one and a half pence for each extra hour that they worked. However, within a week the apprentices felt that they were being cheated and not paid promptly. The managers then decided to share among the apprentices one dollar, (just over four shillings) for each hogshead of sugar that was produced.

The apprentices did not agree with this, no doubt because they did not believe that they would eventually receive the money. The managers also decided that they would organise shifts so the work was carried out over a thirteen to fourteen hour period, with the gangs working alternately in the fields and mills. Robert Pitman was called in to liaise with the workers. In his report he admitted that he thought the demands of the managers were excessive, but he agreed to support them. The results were a week of protests with the apprentices refusing to turn out before six in the morning, the punishment of 128 people, and a full scale riot when some of the offenders were taken to the workhouse.

The apprentices did not agree with this, no doubt because they did not believe that they would eventually receive the money. The managers also decided that they would organise shifts so the work was carried out over a thirteen to fourteen hour period, with the gangs working alternately in the fields and mills. Robert Pitman was called in to liaise with the workers. In his report he admitted that he thought the demands of the managers were excessive, but he agreed to support them. The results were a week of protests with the apprentices refusing to turn out before six in the morning, the punishment of 128 people, and a full scale riot when some of the offenders were taken to the workhouse.

The protest began in earnest on Tuesday 3 March when Pitman sentenced one man from Waterloo estate to two days extra labour for refusing to start work at four in the morning. He then went to Turama to talk to the apprentices. Here the women began chanting 'No! Six to six! Six to six! in reply to his order. Pitman had eight women put in confinement and then ordered the gangs to start work at five each morning. At Orange Hill estate he told the gangs to start work at four. On Thursday, he was summoned to punish the field workers who had turned out late.

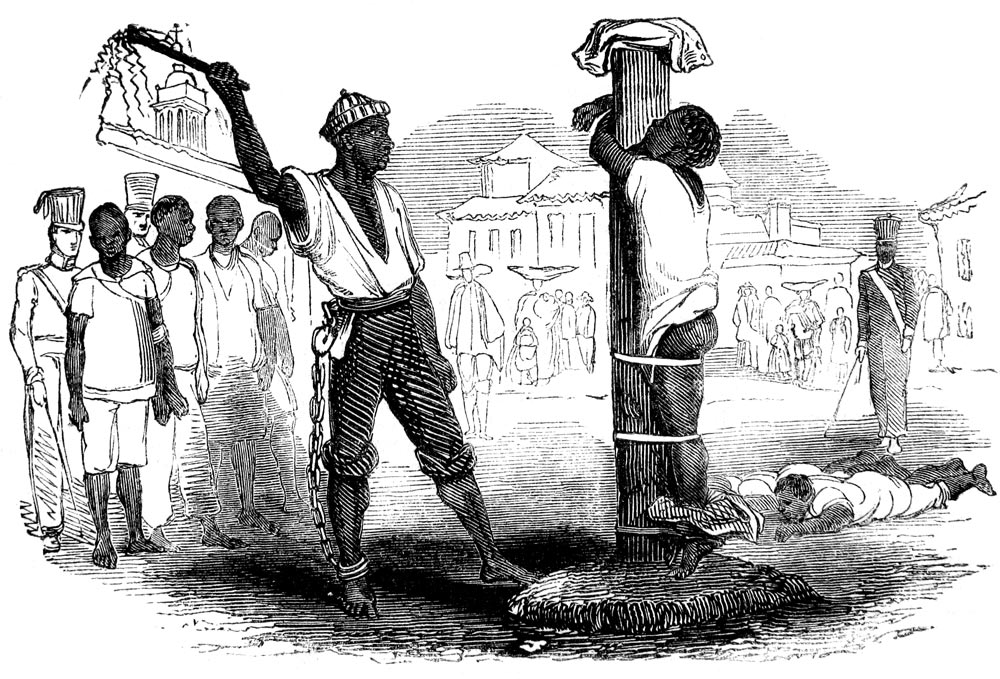

On Waterloo four men and nine women were charged. The women were sentenced to two days extra labour on the estate, but the men were sentenced to forty lashes with the cat. As the men were being flogged one woman, Rebecca, continued to shout out 'Six to six! ' as a sign of defiance. Pitman sentenced her to hard labour on the treadmill for one week. On Orange Hill a similar scene occurred. One woman was held in confinement, but was released because her husband promised that she would behave in future.

A young man was also sentenced to the treadmill for one week for threatening the overseer who had ordered the young man's mother to work in the mill. On Turama, six men and eight women were charged and two men and three women were sentenced to the treadmill for one week. The rest were ordered to work an extra two days on the estate. Pitman had realised the dangers of public floggings. The following day, the apprentices on all three estates refused to turn out before six, and on Turama, they refused to work in the mill. Pitman wrote to the Lieutenant Governor to request extra help and decided to take those sentenced to hard labour off the estates.

The actions of the protesters on these three estates highlight some of the causes of tension within the plantation society. Firstly, the managers decided to change the working hours and forms of payment to suit their own needs without reference to either the previous agreements or the stipulations of the Governor. Secondly, the special magistrate supported the planters despite his own feelings that the hours demanded were extreme. Thirdly, the apprentices reacted immediately to the events, and the field workers were united in their responses and their expressions of their perceived rights.

The women seemed to dominate the protest: they were the loudest and most abusive, yet they received milder punishments. One woman was named as a leader, and Pitman remained convinced that others had taught the women their protest chant. ' He also claimed that the women were 'the primary instigators of the plots. The planters received their demands for long working shifts during the cropping period and the apprentices lost both their protest and their chance for extra wages. The memory of these events remained strong and the repercussions were felt in 1838, when the labourers again attempted to assert their rights and bargain for better working conditions.

Planters were not exposed to the horrors of the cage, treadmill or whipping post, even when accused of murder.

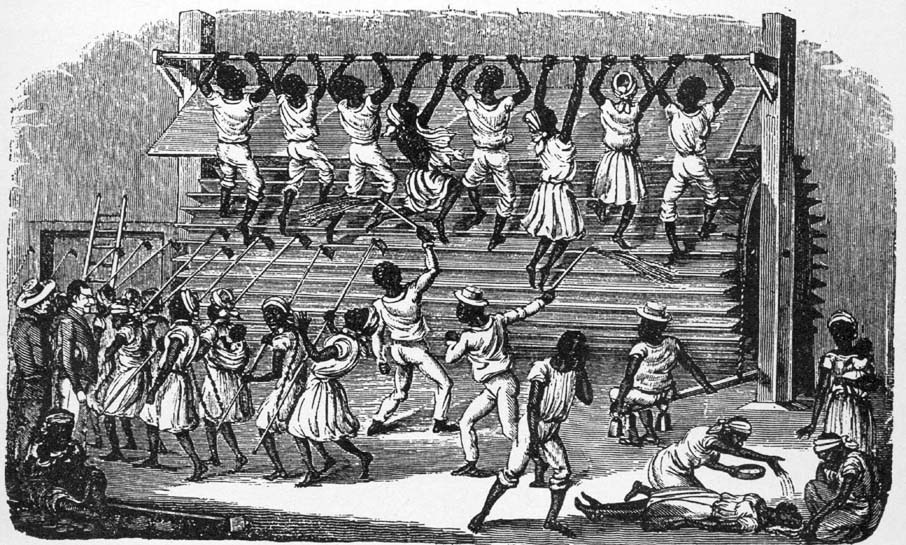

The punishments handed out to apprentices were similar to those they had received during slavery. Women could no longer be sentenced to flogging, but probably continued to be whipped while on the treadmill and within the houses of correction. St. Vincent had houses of correction in Colonarie and Barrouaille, both with solitary confinement cells and space for between thirty to forty prisoners in two rooms. There were also temporary places of confinement in Bequia and Calliaqua as well as prison cells within the estates.

During the day, apprentices, regardless of their sex, age or fitness level, were required to work the treadmill. At night, men and women were separated. The prisoners were supplied with one and a half pints of farine or cornmeal a day and two pounds of salt fish a week. The cage and houses of correction were scenes of degradation and terror for women.

When sentenced, the prisoners' hair was shaved supposedly 'for the better promotion of cleanliness'. This action was noted as being especially traumatic to the women. The authorities mutilated the prisoners appearance and stripped away the women's femininity and individuality. Furthermore, the prisoners were not supplied with any clothing. Hard labour in the penal gangs and on the treadmill tore the prisoners clothes, leaving them effectively half naked. Women were exposed and strapped onto the high treadmills wearing little more than rags.

No female officers were employed in the gaol or houses of correction and rape was reputedly a common occurrence within the houses of correction throughout the British Caribbean, committed by the police guards and the drivers. The most common form of punishment for both men and women was extra labour on the estates. In Kingstown, most of the offenders were classed as non-praedial workers and therefore did not have the same free days as estate workers. Therefore they were punished differently.

Women were far more frequently sentenced to solitary confinement, and this form of punishment, particularly for a protracted period, was considered especially detrimental to the offender's physical and mental well being. Pitman sentenced twenty-one women to full time solitary confinement but only five men, and sixty-five women and eighteen men had sentences of solitary confinement after work on their estates. The use of solitary confinement and corporal punishments, including the treadmill, were all aimed at breaking the prisoners' rebelliousness through a combination of humiliation, physical pain and fear. They emphasised and strengthened class and race hierarchies, by imposing different forms of punishment on different classes of people. Planters were not exposed to the horrors of the cage, treadmill or whipping post, even when accused of murder.

Although the abolition of slavery had reduced the hours of work that labourers were compelled to work, men and women continued to be expected to perform arduous tasks on the sugar estates. On many estates, the apprenticeship period caused few problems and the managers and labourers were able to cooperate with each other. On other estates, notably Arnos Vale, Cane Hall, Struam Cottage and Fountain estates in the southern district and Richmond estate in the leeward district, conditions for the apprentices were excessively harsh and relations were tense and angry. These were among the estates to experience wage and labour disputes after 1stAugust 1838. Furthermore, the St. Vincent apprentices received a higher proportion of punishments than apprentices in Barbados.

Throughout the British Caribbean, the apprenticeship period failed its primary objective of preparing the ex-slaves and their employers for a harmonious free labour economy. This was mainly because of the intransigent and hostile actions of the planter class and the weakness of the mechanisms put in place to protect the apprentices.

Throughout the British Caribbean, the apprenticeship period failed its primary objective of preparing the ex-slaves and their employers for a harmonious free labour economy. This was mainly because of the intransigent and hostile actions of the planter class and the weakness of the mechanisms put in place to protect the apprentices.

Magistrates frequently sided with planters and imposed heavy fines and excessive punishments on labourers. The use of the whip and the treadmill, heavy reminders of the degradations of slavery, further widened the divisions between the different races and classes. Although planters and magistrates complained that labourers were not working steadily throughout the apprenticeship period, the quantity of sugar that was produced increased.

It is especially noticeable that women suffered excessively during the apprenticeship period. Although they could no longer be whipped by drivers and overseers, they continued to be overworked and unduly punished. Child-care became an additional burden for women on the estates, as many lost both the facilities of the nursery and the free food and clothing allowances they had received as slaves. However, despite all the restriction imposed on them, the mothers of young children earned a major victory over the planters. Nearly every-one of them retained control over their children's future by refusing to allow them to be apprenticed onto the estates. This ensured that, when apprenticeship ended in 1838, all African-Caribbean labourers were freed from any form of indenture and could dictate their own choice of work and residence.

Adapted from COLOUR, CLASS AND GENDER IN POST-EMANCIPATION ST.VINCENT,1834-1884 by Sheena Boa.